“That’s a great idea. We should gather more information on it. Do some more interviews and research, pull additional data, see what it all tells us. I like the direction though.”

While those may feel like encouraging words, to me they were another nail in the coffin. We had gone around and around for weeks, and were getting no nearer to a resolution or way forward.

“Can you help me understand what more you’re looking for? We’ve got all the data here. We’ve analyzed the opportunity and feel like it’s interesting, at least to try out. Nothing big, like we’ve discussed.”

“I’ve got to run to another meeting, but sync up with Sandy in reporting. She can help you get what you need.”

And with that, at least another two weeks would go by. I had done the research, pulled the data, looked at the market, and plotted out a potential path. But it wasn’t enough. It would never be enough.

More interviews and research and data were a simple way to procrastinate deciding. And so it goes. We continue with our meetings and our research until one of us eventually gives up, either on doing the research or coming to the meetings.

You may recognize my (slightly) dramatized scene above. I’ve been in a variation of that situation many times. We have ideas for features or experiments or new processes we want to try, but they die as ideas.

Because we get stuck in analysis paralysis.

We get frozen over-analyzing an idea to the point that we never take action on it. Or we get stuck doing so much research and planning that we delay any action for weeks or months.

Occasionally this is good, like when you have a huge or important decision that you can’t undo. But most of our decisions aren’t like that. We make better decisions by acting.

Paralysis by Analysis

What does this look like and what causes our paralysis? Our failure to act?

Difficulty Parsing Signal vs. Noise

We live in a time of information overload. I wrote about it in an article called Signal vs. Noise, and it grows truer every day.

It is so easy to get lost in information. We’ve never had more information or easier access to data. And that is only increasing rapidly. The IDC estimates that we’ve gone from 1.4 zettabytes (1.4 trillion gigabytes) of data in 2010 to around 40 zettabytes of data in 2020. We’ve nearly doubled our digital data every 2 years, which is amazing. And incredible to think about in the future.

It is also daunting because there is no end to how much we can research and learn about any topic. But how much of that information will be valuable? Sorting the signal from the noise is difficult, and often causes us to stop acting and only do more and more researching.

Confusing Motion with Action

In his book Atomic Habits, James Clear relates the story of a group of students at the University of Florida in a photography class. The professor divided them into two groups at the beginning of the semester. One group would be graded on the quantity of their work, the other on the quality. So the group that would be graded on quantity got to work taking lots of pictures. The group that only had to produce one quality photo spent the semester researching and speculating about the “perfect” photo.

In the end, the group that focused on quantity also produced the highest quality. They got the reps in, practicing with composition and lighting, until they perfected their art in a way that you can’t do by talking about it.

“Motion makes you feel like you’re getting things done. But really, you’re just preparing to get something done. When preparation becomes a form of procrastination, you need to change something. You don’t want to merely be planning. You want to be practicing.”

No Direction or No Map

If you don’t know where you’re going or where you want to go, it’s easy to feel you need to analyze everything before you decide.

I’ve seen this before. I’ve been part of several companies that didn’t have a clear strategy or vision. So no one was sure what exactly to do. And felt like they needed to protect themselves by analyzing everything extensively before moving forward. That way they could avoid taking any risk, or distribute the risk enough that no one would have to take too much blame if things went wrong.

And even if you know where you want to go—you have a vision and strategy—you may not have a clear path for getting there. You know you want to write NY Times bestseller, make a million dollars, or start a business, but know nothing beyond that.

Breaking down your vision to actionable steps is often the map, but without that you’re often left paralyzed by indecision. Like the students above, you don’t know exactly how to move forward with taking the best picture, so you theorize about it and never do it.

Paralyzed by Fear

We fear being wrong. We fear how we may look or how others will perceive us if we make the wrong decision. We often expect ourselves to be experts at everything, so anything that would take away from that we want to avoid.

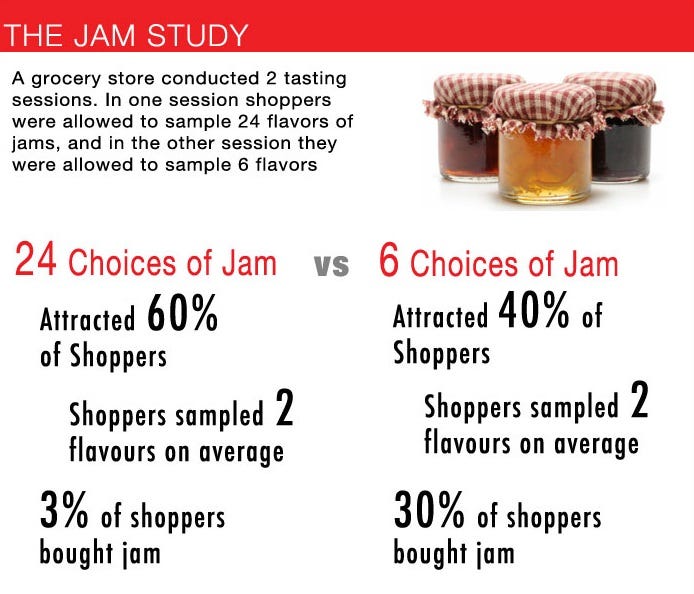

We also fear the number of choices. In a fascinating study, known as the Jam Experiment, researchers wanted to see if more choices affected the behavior of people. So buyers at a local grocery store saw either a selection of 24 jams for a taste-test, or 6 jams. The results were interesting. The 24 jam selection attracted more attention, but was overwhelming to buyers, who purchased less jam. The 6 jam selection got less attention, but shoppers bought more jam.

When we get overwhelmed by the number of choices, we struggle to decide, and will often not make any decision.

Path of Least Resistance

Doing nothing is the path of least resistance. And we find refuge in analyzing all the options but changing nothing.

I’ve seen analysis paralysis used to avoid change. In one instance, one of my teams was asked to spend several months analyzing between vendors. We had already done this exercise once and made a selection, but the company wanted us to do it again. So we spent months analyzing pros and cons, benefits and costs. Each round of analysis would raise more questions. Eventually we spent so much time doing research, that it was too late to actually change which vendor we were using, so we ended up going with our original choice, anyway.

It’s easy to get caught up researching, analyzing, and thinking about ways to tackle problems. But until we actually start working on them, we can’t solve anything.

The Antidote - Taking Action

If the issue is paralysis, then the antidote is action. But how can we break out of overthinking and move forward? How can we get ourselves, our teams, or even our companies to stop over-analyzing decisions and start taking action?

Prioritize Decisions

Some decisions we need to take slow, but most decision we can move quickly on and walk back if necessary. We need to understand the difference and prioritize our decisions.

I wrote about Jeff Bezos and Amazon recently, and they have a good approach for this. In a shareholder letter, Bezos shared this idea:

“Some decisions are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible -- one-way doors -- and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and don't like what you see on the other side, you can't get back to where you were before. We can call these Type 1 decisions.

But most decisions aren't like that -- they are changeable, reversible -- they're two-way doors. If you've made a sub-optimal Type 2 decision, you don't have to live with the consequences for that long. You can reopen the door and go back through. Type 2 decisions can and should be made quickly by high judgment individuals or small groups.

As organizations get larger, there seems to be a tendency to use the heavyweight Type 1 decision-making process on most decisions, including many Type 2 decisions. The end result of this is slowness, unthoughtful risk aversion, failure to experiment sufficiently, and consequently diminished invention. We'll have to figure out how to fight that tendency.”

Most of our decisions in organizations and product teams are Type 2 decisions. We don’t need to treat them like Type 1, one-way doors.

Timebox Your Research

I love to research and learn. I could spend most of my time researching and learning new things if that were an option. But it isn’t.

If you’re familiar with Parkinson’s Law, it states that work will expand to fill the time allotted. That goes for research too. So you need to timebox, or put a time limit, on how much you will allow.

You will never learn all you need to know. When I was first learning wood turning, I spent an inordinate amount of time reading and watching videos. That was great to a point. I needed to understand the basics of what to do. But I also needed to put a limit on how much time I watched videos vs. how much time I spent at the lathe. I initially erred on the side of too much research until I finally got myself into the garage turning wood. It was ugly in the beginning, but got much better with practice. I still watch videos and do research, but I spend much more time doing than researching.

Do and Iterate

Like timeboxing your research, you need to do something and iterate on it. If you only watch videos of other people wood turning, you can never do it yourself. Once you do something, you then have an understanding you can build on and iterate on. The videos of others will have more meaning because you will see how their hands hold the tools different from you, how they make passes at the wood, how they avoid tear out, etc.

The same principles apply to creating anything. No amount of user interviews (as important as they are) can help you more than actually building some simple working software. Because no one knows what they really want or how they’ll interact with something until they actually interact with it. It doesn’t have to be a year-long project, but simple working software will beat talking and thinking about data.

Embrace Being Bad (and Good Enough)

When we begin any new endeavor, we are going to be bad at it. You didn’t begin walking by strutting your stuff. So you need to embrace the fact that you won’t be great at everything you do. But with time and practice, you will get better.

Additionally, not every decision has to be perfect. Herbert Simon labeled this “satisficing”. His research suggested that we can either find a solution that is good enough for our needs, or continue attempting to find a “perfect” solution.

Unfortunately, those who try to “maximize”, or find the ideal solution, take far longer to settle on a solution and are far less happy than those who satisfice, or find a solution that will work well for the constraints, and move forward.

Make Your Decision The Right One

There are often many “right” decisions to a problem. Unlike school, the real-world is not a series of problems with answers at the back of the book. So we shouldn’t spend our time fretting if we got it right.

We should make it right.

In a great article about this topic, Becky Kane, referencing HBR, suggests we make our decision the right one.

“We overemphasize the moment of choice and lose sight of everything that follows. Merely selecting the “best” option doesn’t guarantee that things will turn out well in the long run, just as making a sub-optimal choice doesn’t doom us to failure or unhappiness. It’s what happens next (and in the days, months, and years that follow) that ultimately determines whether a given decision was ‘right.’”

Analysis paralysis can kill some of our best ideas and our best work. But it doesn’t have to be that way. We can avoid “death by data” by taking action. Even small actions. And then use our research and learning to iterate and improve along the way. It won’t be perfect, because nothing is. But movement in the right direction will always be better than lots of good intentions.

Good Reads and Listens

Groupthink: Recognizing It In Teams and Organizations (article) - Unfortunately, groupthink continues to be pervasive on our product teams at every level. Whether it is minor features or big launches. Sometimes it is a poorly designed product. Sometimes it is a tragedy. But at the core, we can often find groupthink, which is why we need to understand it, recognize it, and avoid it.

NFTs and A Thousand True Fans (article) - You probably saw this if you’ve been following the NFT hype, but if not, it’s a great read. I’m excited about NFTs and their potential now and in the future. They are still very raw, but we’re seeing all sorts of experiments.

User Personas (podcast) - Personas can be great in theory, but in practice can fall short. In this episode, we explore the ways to use personas and the ways they can fall short, along with what to do for your teams.