Groupthink - Understanding and Avoiding It

Recognizing the Symptoms, Seeing the Bias, and Making Better Decisions by Avoiding the Pitfalls

One of the most classic cases of groupthink was the Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961. During this episode, the CIA trained Cuban exiles to return to Cuba to overthrow the Castro regime.

President Eisenhower organized the operation, and President Kennedy inherited it. The U.S. planned on financing the dissidents, providing support, and sparking a counter-revolution in Cuba.

Despite misgivings, no one spoke up against the plan. And it turned into a massive failure. The Cuban military quickly routed the dissidents, and the U.S. pulled support while the exiles surrendered. It was a classic case of groupthink. Everyone thought it was a bad idea, but no one was willing to say anything, and so the plan progressed to its inevitable end.

This is the culmination and summary of our discussion on groupthink. I’ve aggregated some of the previous discussion, but don’t forget to go back and check out the previous posts for more.

Working in Groups

We often think working in groups will help us do better work. It’s why we have teams at work and in school, right? We expect the group to curb individual biases and make better decisions.

Group Polarization

Unfortunately the opposite can be true. Individual biases can get amplified in groups. We know this as group polarization.

As a group talks and works together, it may move to a more extreme consensus. They have shown this experimentally. In the link above, the authors tested out the theory with some hot-button political issues, bringing together people from either left-leaning or right-leaning backgrounds. After grouping them with similar thinking members, not only did the group get more extreme, but individuals reported more extreme personal views as well.

Hidden Profiles

When we bring a group together, we will often get the information that most members have. But a serious problem is that information that a few members may have could stay hidden. If 12 group members all know something, but two of the group members have some additional information that would be useful, it’s likely that those two will stay silent.

This is like the shared information bias and happens together with it. We focus on the information we all share in order to reach a consensus rather than the information that only a few may have that may be more consequential.

Conditions for Groupthink

Irving L. Janis was a pioneer in the study of group dynamics and coined the term “groupthink” in 1971.

He described three fundamental conditions that make groupthink more likely:

A highly cohesive group where there are no longer disagreements and members are deindividualized

Structural faults such as a leader with a preference for a certain decision, insulation of the group from outside opinions, or homogeneity of members

Situational contexts such as highly stressful external threats, recent failures or time pressures

Symptoms

Janis also identified eight major symptoms of groupthink, and grouped them into three categories:

Type I: Overestimating the power and morality of the group

Illusions of invulnerability creating excessive optimism and extreme risk-seeking.

Unquestioned belief in the group’s morality, causing members to ignore the consequences of their actions.

Type II: Closed-mindedness

Rationalizing warnings that might challenge or discount the group's assumptions.

Stereotyping those who oppose the group as weak, evil, biased, spiteful, impotent, or stupid.

Type III: Pressures toward uniformity

Self-censorship of ideas that deviate from the apparent group consensus.

Illusions of unanimity among group members, silence is viewed as agreement.

Direct pressure to conform placed on any member who questions the group, couched in terms of "disloyalty"

Mindguards— self-appointed members who shield the group from dissenting information.

The Tragedy

In the tragedy of Columbia, the Bay of Pigs, and most other classic cases of groupthink, most factors listed above were present.

The conditions for groupthink were right. It was a cohesive group with structural faults and outside pressures.

But as you dive deeper, you can see the symptoms as well. The group apparently had an attitude of invulnerability. There was self-censorship within the team, pressure to silence criticism and guards against dissenting information. Rather than ask “what could go wrong”, they were only looking at the best scenarios and assuming everything would go right.

Groupthink in Product Teams and Organizations

Who could have ever thought that was a good idea?

There are so many products I ask that question about. You probably do too. One classic example (forgive the pun) is New Coke. And what makes it great is how it was riddled with groupthink throughout - on both sides.

For those unfamiliar with the story, New Coke was introduced in April 1985. Coca-Cola, the flagship drink, had been losing ground for years, so the company decided to change its 99-year-old formula to make it sweeter and more modern.

It was a bold move they had tested and researched extensively. Unfortunately, it was almost as if the team working on it had decided it was the right move and was willing to ignore information to the contrary. There were many focus group participants who hated the idea of changing the formula and were passionate about it. But they rationalized those opinions away before the launch.

The executives in charge almost seemed to think they were infallible in what they were doing. Not only that this was the right move, but they were sure enough to bet the entire company on it. They didn’t position New Coke as a new offering alongside Coke and Diet Coke, but a wholesale replacement of Coca-Cola.

Once they had made the move and launched New Coke, it was initially well-received by most of America. We remember the whole thing now as a fiasco, and there were plenty of diehard Coke fans who were shattered by the change, but most people liked the fresh taste. That didn’t stop the jokes and strong opinions, however. And it led to mounting pressure on Coca-Cola.

Just like the dissent that had been quieted with the introduction of New Coke initially, as the tide turned against New Coke, any support of it within the Coca-Cola company also became self-censored. Those leaders who preferred New Coke could not voice that opinion because of the peer pressure mounting to return to the old Coke formula.

In the end, New Coke went down in history as one of the biggest blunders for a product. After 79 days, Coca-Cola reversed itself and reintroduced its classic Coca-Cola, killing New Coke. There are many lessons to learn from it, one of which is that suppressing information or dissenting views will always lead to worse outcomes.

My opinions with cola aren’t nearly as strong. I personally prefer Pepsi Zero, but also like Coke Zero and Diet Pepsi. You can take Diet Coke and throw it in the dumpster. Maybe I do have some strong opinions.

Regardless, we’ve all probably seen or worked on teams that have had issues with groupthink. And our products and product experiences suffer because of it.

We’ve seen how groupthink impacts organizations. And from New Coke, how it can derail a tried-and-true consumer product.

So how else does groupthink manifest in product development?

The HiPPO

For those unfamiliar with the term, HiPPO stands for Highest Paid Person’s Opinion. The HiPPO is usually a leader or an executive with authority in your area or even outside of it. And when they speak, everyone listens and obeys, even if it’s not the best course of action.

We can (and probably will) write a lot more about HiPPOs. But for now, this is one way that groupthink can take over our decision process. If the CEO or SVP of marketing is in your meeting, and says that they would like to see the application done in a certain way, it often takes the rest of the air out of the room. Depending on how strong of a personality they have (and you have), this may be the last word on the matter.

This is one of the structural faults identified by Irving Janis in his work on groupthink. When you have an impartial leader, there is often little room for dissent or criticism and the deck gets stacked, often insurmountably.

Abilene Paradox

The Abilene paradox comes from Jerry B. Harvey and is characterized by a group of people collectively agreeing to a course of action counter to the preferences of each individual.

The paradox starts with someone suggesting that a group drive to Abilene, which is 50 miles away, for a meal. The road is long and hot, and this was before cars had air conditioning. No one in the group wants to go, but each agrees, not wanting to dissent. So they all go, have a mediocre meal, and complain about it when they get back. Only then do they realize that none of them wanted to go, and even the person who suggested it only did so because he thought the others were bored.

How often do we see this on our teams? Not wanting to rock the boat, we self-censor or go along with the group, assuming that if everyone else is in agreement, then it can’t be that bad of an idea.

I’ve been guilty of this enough times to know that going along with the group, even when they are confident, isn’t enough to get my buy-in. Which is why I try to make a habit of questioning team decisions, especially early on.

When I came into a new team several years ago, I didn’t do this. We were well into the development of an additional feature for a product, and it seemed like everything was moving along. So I didn’t ask enough questions. I hopped into the car to Abilene and we kept driving. And it came back to bite me. Nothing about the feature turned out like we had hoped. And everyone knew it in hindsight. But none of us had stopped it. Don’t let that happen to you.

Design By Committee

Groups are meant to help us make better decisions, but often the opposite can happen. We’ve talked about this, and how groups can drive us to more polarized opinions. But the opposite is also true.

When we create a new product of feature, we often set out with a bold vision or strategy. But depending on your company or organization, that bold vision gets put through multiple cycles of de-boldifying. Everyone has to have their say, so what was once a focused idea becomes a mish-mash of everyone’s wishlist.

This happens with products, with features, with roadmaps, with strategies. And is often worse the bigger the group. Rather than a focused, bold direction, you end up with something designed by a committee. And it shows.

The Roadmap or Project Plan

Another cause of groupthink in our product teams is the roadmap or project plan. Which is why we love and hate roadmaps, as I’ve written about before.

The cause of this problem is the time pressure that a roadmap or plan puts onto a group. While a roadmap shouldn’t be a firm commitment to a date, that is often how it is viewed by leaders or other stakeholders. And they often hold teams to those commitments.

Once time pressures are introduced, many groups fall into the trap of groupthink. Rather than question assumptions or look for alternative paths, they will follow the plan. And everyone will go along with it. Because it is easier to go with the flow than rock the boat.

We’ve all been there before. I know I have. We’ve made a commitment. And while things may have changed, the easier path is simply to deliver the feature than to get everyone to understand why it would be better to pivot. Or (heaven-forbid) delay. I’m certainly no longer afraid of those conversations, and even relish them more than I should because they give me a chance to help others understand roadmaps and product thinking better, that’s not always an option for everyone. And it’s a pitfall for groupthink.

Lack of Methodology

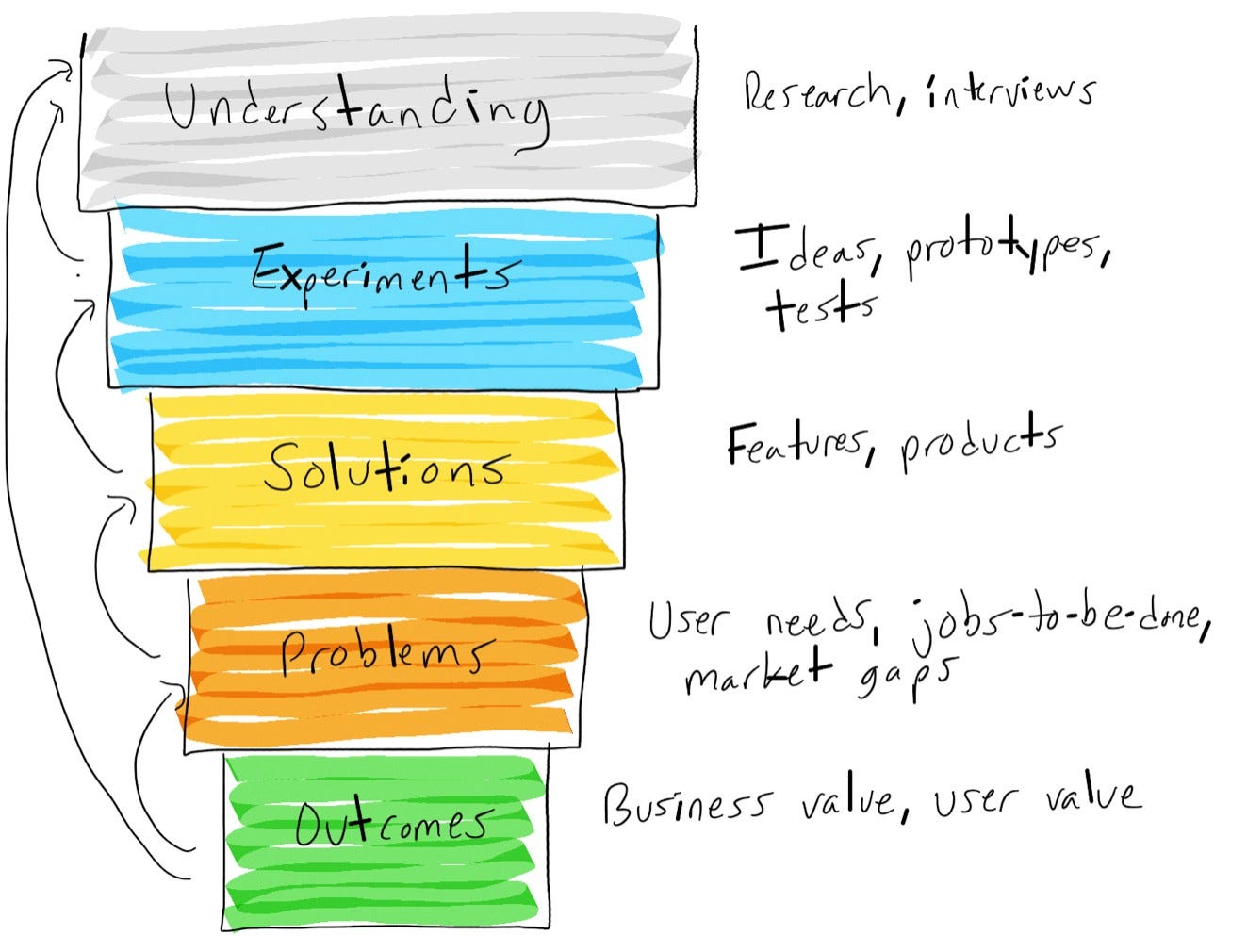

When teams don’t have processes or methodologies to guide their decisions, it is far easier to fall into groupthink.

This was another cause identified by Janis in the 1970s. And it is just as relevant today.

Good product teams have a process for making good decisions. And for creating excellent products. That should involve research and discovery, time of iteration and learning, and repeating the process.

Unfortunately, many product teams don’t have some or all of these methodologies. Discovery may not be part of the process. They may be handed features to develop from an executive team who thinks they know best. Or they may not have time to learn and iterate, having to move from one thing to the next.

Good product management is about helping teams have good decision processes. Forcing us to think about what we’re doing and why we’re doing it. If we don’t do that, we often move too quickly, not questioning our assumptions, relying on the HiPPO or the project plan or the loudest voice in the group. None of which make for a good product experience.

New Coke wasn’t a massive aberration, it was just at a massive scale with a beloved product. Unfortunately, groupthink continues to be pervasive on our product teams at every level. Whether it is minor features or big launches.

Avoiding Groupthink

We’ve identified the various traps of groupthink over the past few weeks. From identifying Groupthink to Groupthink in Organizations and Groupthink in Product Teams. Now we will take a closer look at avoiding falling into these common traps.

Good Leadership

Picture this scenario. You need to make an important decision about priorities. A new opportunity has come up and displaced some existing work. So you go into a meeting with key decision-makers. After some discussion about the problem, you go around the room to decide how to prioritize the work. The executive and the salesperson for the new business are passionate about it, so they talk about it first and how important it is and time sensitive it needs to be. Everyone agrees with that assessment as you go around the room, so you now have your new direction.

Or do you?

This is a classic trap, and one that I knew we could fall into recently. So in a discussion, I sent out a questionnaire before our meeting to get everyone’s opinion about the order of priorities. I wanted to understand what each person thought before we discussed and before other leaders or participants could sway things one way or another.

This is an important tactic for avoiding groupthink, especially for leaders. If you are a leader, before you tilt the scale, you need to understand what others are thinking. Because, like Expensify above, there is a good chance that your enthusiasm for an idea may lead to a specific direction whether or not everyone else agrees with that. So understanding that before you speak is critical.

Outside Expertise

Any single person can be wrong. You can be wrong. Your team can be wrong.

It’s easy to get into our own heads. We’re often the experts in our area, especially if we’ve been doing something for a long time. That can be an amazing thing, but also a dangerous thing. Because with expertise, we bring bias. Especially within our businesses. We have a stake in certain outcomes, whether or not we realize it.

In my current company, we have a vested interest in people being in the office. So that led many people to think, especially early in Covid-19, that the crisis would pass quickly and people would return to their offices soon.

A great way to avoid groupthink is to get outside expertise. Not a single outside expert, but a variety of outside opinions averaged together. A variety of voices that can help you understand different sides of the problem. If you are a product manager, listening to your users is critical here. But also listening to other experts in the industry.

Even if we can’t get outside experts, we can take an outside view. Daniel Kahneman, in his book Thinking, Fast and Slow, famously recognized this when working on curriculum and a textbook for the Israeli Ministry of Education. The group was incredibly optimistic about their timeline, expecting to finish within two years. Kahneman then asked one of the group if anyone undertaking a similar project had succeeded that quickly. The answer was that most groups took an average of 7 years, if they ever finished at all. That was a hard realization for the group, and one they should have heeded, but ultimately didn’t.

The key was that the group took an outside view. What had other groups done? What was an outside perspective rather than our group perspective?

Deliberate Debate

I am a huge proponent of debate on teams and within organizations. Cultivating a culture of debate is one of the best things you can do to foster creativity and avoid groupthink.

I wrote about the pitfall of not having a culture of openness previously. But how can you create deliberate debate?

One way is to create a red team. In one organization I worked in, we had the practice of deliberately creating red teams, whether groups or individuals, who had the responsibility to thoughtfully oppose big decisions and analyze ways they could go wrong. Often they would be known as supporters of the decision, but we expected them to look deeply at how things could go wrong and bring all of those things to the surface.

In another organization, we already had a culture of debate, so you could expect everyone to take the role of the red team. That meant that for big decisions or proposals you’d have to come prepared to discuss and defend. It was not meant to be a personal attack, but to flesh out weaknesses before they became colossal problems. And it was successful. It was incredibly stressful initially, but I learned to love those debates and discussions. I became my own red team, looking for weaknesses before others could so I could strengthen my own proposals.

“What Are We Missing” Mindset

I don’t do a lot of driving right now, but when I was commuting each day, I tended to drive a little faster than the speed limit. Some of you might do the same. But whenever I was passing a group of cars going a lot slower than I was going, I always asked myself, “what am I missing?” It worried me that they might know something that I didn’t, like there might be a highway patrol ahead.

We should constantly ask ourselves, “what are we missing?” That’s excellent advice for driving down the road, especially if you’re speeding, but it’s better advice for a group or team. What are you overlooking? What aren’t you thinking about?

This goes into becoming our own red team. We need to identify potential pitfalls before they become issues. If you’re ever in a room or group where everyone agrees, pause the discussion because you’re undoubtedly missing something.

Methods For Decisions

Having a method for making decisions is a key for avoiding groupthink.

On good product teams, this is a product discovery process. It’s easy to give into the loudest voice or the highest paid person’s opinion. But if you have a good process in place, you don’t fall victim to that kind of thinking.

In one product I was working on, we had a solid process in place. The executive, who had incredible experience in the area, wondered why we weren’t doing things in a certain way. I pulled out the user research I had done along with the data we had collected to show why we were doing it differently, and showed that despite what some people were saying, the way we were doing it would be a better experience for users and better for our company. That was the end of the discussion.

With good processes in place, you don’t fall victim to groupthink, but can apply the right methods and come to the right conclusions.

Team Dynamics

One of the biggest problems in groupthink is the group itself. If you have a highly cohesive group, you are at risk for groupthink. Especially if that group has been together for a long time.

I’ve seen this firsthand. Teams that have worked together for a long time with similar industry experience in the same company (like for the last decade) are ripe for groupthink.

The best thing you can do is inject diversity into that group. That includes outside perspectives, new to the company or new to the group, and unique experiences and backgrounds. But it also includes changing how the group functions. If you are a leader observing a group, you need to ensure you are getting the right dynamic. If possible, you want to get people willing to debate and express opinions, as well as people who can balance the social interactions of the group to get the best outcomes and participation.

Research shows that women will be critical to this, and my personal experience has proven that out. I was recently in a group that was tailored for achieving an outcome. It had a perfect mix of new perspectives and old experience. It had varying disciplines, men and women, and different temperaments. It was amazing the results we achieved in a short time.

Groupthink happens to all of us. But as we learn to recognize it, we can put guards in place to avoid the most common pitfalls. As leaders, we can help our teams by creating the right environments for the best decisions and outcomes. And when we see groupthink happening, we can help correct it before we email 10 million people or launch the next New Coke.

Good Reads and Listens

Building Trust and Effectively Working Across Disciplines (podcast) - We interviewed Ali Maquet, a Principal Portfolio Manager. She's had an array of experience, from working as a BA, a scrum master, a PM and now a portfolio manager. She gives advice for moving into new roles, shaping your role, working with different disciplines, & building trust.

5 Major Innovations We’re Thankful For (podcast) - 2020 has been difficult, but that doesn't mean we can't be thankful for some major innovations that make life better. In this episode, we take a look at some stories behind some of our favorite things. From wristwatches to cameras, and the stories of Alberto Santos-Dumont to Jonas Salk, buckle up for some fascinating tidbits behind that make 2020 a little more bearable.

Apollo’s Arrow: The Profound and Enduring Impact of Coronavirus on the Way We Live (book) - I read this book this past month and it was a great summary of the coronavirus in 2020, where we are, and what comes next. It feels like ages ago when this all began, but it wasn’t that long ago. But we still have a way to go. And we’ll continue to need good people and good leaders to get through.